Using the broad powers granted under the USA PATRIOT

Act, the FBI demanded that 4 librarians produce private information

about library patrons’ reading habits, then used an endless gag order to

force them to remain silent about the request for the rest of their

lives under penalty of prison time.

In July 2005, two FBI agents came to the office of the Library

Connection, located in Windsor, Connecticut. The Library Connection is a

nonprofit co-op of library databases that arranges record-sharing

between 27 different libraries. It facilitates book rental tracking and

other services.

The FBI handed Library Connection’s executive director George

Christian a document which demanded that he produce “any and all

subscriber information, billing information and access logs of any

person or entity” that had used library computers between 4:00 p.m. and

4:45 p.m. on February 15, 2005, in any of the 27 libraries whose

computer systems were managed by the Library Connection.

The FBI was demanding that the library hand over private data on

library patrons en masse “to protect against international terrorism.”

The document that Mr. Christian was given was a so-called National

Security Letter (NSL), a type of administrative subpoena for personal

information — self-written by the FBI without any probable cause or

judicial oversight. The legal framework for these powerful NSLs was

established by Section 505 of the USA PATRIOT Act in 2001.

What’s more, Mr. Christian was placed under a

perpetual gag order.

The NSL prohibited the recipient “from disclosing to any person that the

F.B.I. has sought or obtained access to information or records under

these provisions.” The gag order was broad enough that it was a crime

to discuss the matter to any other person — for life. The USA PATRIOT

Act allows for this suppression of speech, and issues a punishment of up

to 5 years in prison for anyone caught violating the endless gag order.

When Mr. Christian received the NSL, he was unsure about whether or

not he could even consult a lawyer or his board of directors.

Technically, the gag order did indeed prevent any such discussion.

The only reason we know about this case today is because Mr.

Christian and 3 other library board members fought back in court. The

other librarians involved were Barbara Bailey, president of the Library

Connection; Peter Chase, vice president of the Library Connection; and

Jan Nocek, secretary of the Library Connection.

The ACLU took up their cause and challenged the validity of the gag order in court. The librarians became known as the Connecticut Four,

but could not individually identified for many months. In suing U.S.

Attorney General Alberto Gonzales, they could only be named “John Doe”

and were required to remain in silence about the case under threat of

prison time.

The case was known as

Doe v. Gonzales.

The lawsuit stated that the Library Connection “strictly guards the

confidentiality and privacy of its library and Internet records, and

believes it should not be forced to disclose such records without a

showing of compelling need and approval by a judge.”

The four librarians under the gag order were not allowed to communicate with each other by phone or email, and were not even allowed to tell their own families about the case.

In fact, the librarians were even barred from attending the court

hearings on the very precedent-setting lawsuit with which they were

involved.

The Case stated by Mr. Christian :

When we first sued the Attorney General, I told our

attorneys I’d like to be in the courtroom. After all, I’m the plaintiff.

And they said no. They had talked to the judge. That would not be

allowed, because then our identity could be guessed. But the judge did

allow us to go to a courtroom in Hartford, sixty miles away, where we

were locked in a room with a security guard and able to watch our case

on a monitor. But as the plaintiffs, we were not allowed in the

courtroom.

…The release of our identity would be considered a national security

threat, because, they reasoned then, whoever they were interested in

would realize that the FBI was closing in, although, with twenty-six

libraries, I doubt they could really make that a case. We did get to

attend the appellate court, along with Nick Merrill. We didn’t know at

that time whether Nick was a male or a female. We were instructed to

enter the courtroom in New York independently, to enter the building

independently, not to sit with each other, not to have eye contact, not

to have eye contact with our attorneys. But at least we could

participate in the audience and watch our case being argued.

“Our presence in the courtroom was declared a threat to national security,” Mr. Chase related.

The gag served to legally prevent Mr. Christian from personally

testifying before Congress about the effects of the USA PATRIOT Act

before the law’s reauthorization in March of 2006. It passed through

Congress easily and was signed once again by President George W. Bush.

Appellate judges were clearly disturbed by the breadth of the NSL gag

provisions. One appellate judge wrote, “A ban on speech and a shroud

of secrecy in perpetuity are antithetical to democratic concepts and do

not fit comfortably with the fundamental rights guaranteed American

citizens… Unending secrecy of actions taken by government officials may

also serve as a cover for possible official misconduct and/or

incompetence.”

Sensing a potential legal defeat, the government took the steps

necessary to preserve its powers. Only a few weeks after the USA

PATRIOT Act was renewed, the FBI abandoned the Library Connection case

and voluntarily lifted the librarians’ gag order. This eliminated the

possibility that the NSL provisions could be struck down in court,

protecting the USA PATRIOT Act from further judicial scrutiny. In May

2006, the four librarians broke their silence at last.

“

As a librarian, I believe it is my duty and responsibility to speak

out about any infringement to the intellectual freedom of library

patrons,” said Mr. Chase. “But until today, my own government prevented me from fulfilling that duty.”

“By withdrawing the gag order before the court had made a decision, they withdrew the case from scrutiny,” Mr. Chase said.

Ms. Nocek described the dilemma to a reporter:

“Imagine the government came to you with an order demanding that you

compromise your professional and personal principles. Imagine then being

permanently gagged from speaking to your friends, your family or your

colleagues about this wrenching experience… Under the Patriot Act, the

FBI demanded internet and library records without showing any evidence

or suspicion of wrongdoing to a court of law. We were barred from

speaking to anyone about the matter and we were even taking a risk by

consulting with lawyers.”

“The fact that the government can and is eavesdropping on patrons in

libraries has a chilling effect,” said Mr. Christian, “because they

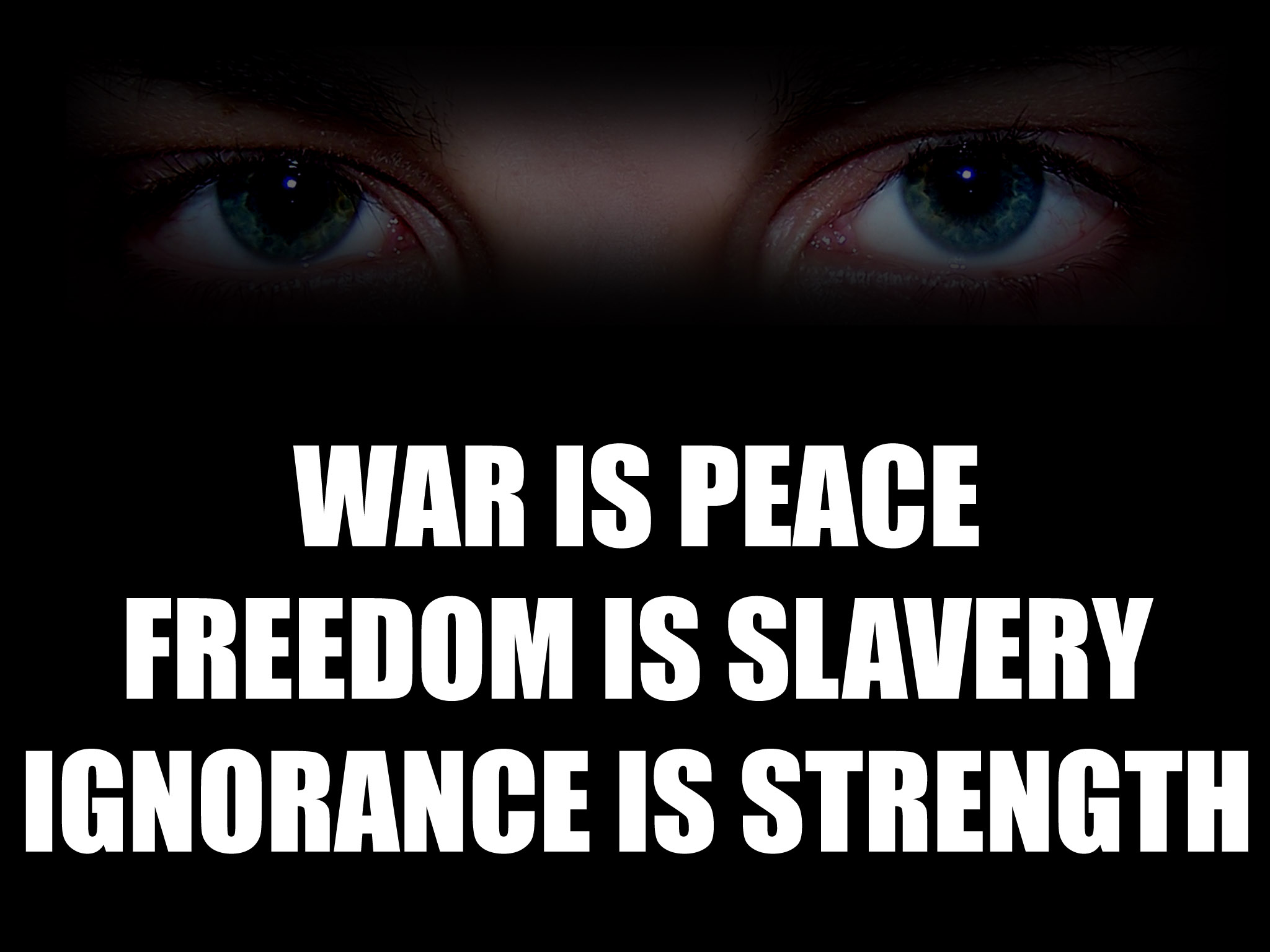

really don’t know if Big Brother is looking over their shoulder.”

“While the government’s real motives in this case have been questionable from the beginning,” said Ann Beeson,

Associate Legal Director of the ACLU, “their decision to back down is a

victory not just for librarians but for all Americans who value their

privacy.”

The ACLU is WRONG....It wasn't a victory, it was a defeat for all Americans...BECAUSE if it had be adjudicated in a US Court and found to be unconstitutional the NSL provisions could be struck down in court thus

protecting all AMERICANS from the Draconian USA PATRIOT Act.

The FBI won their victory by keeping the NSL Letter from becoming illegal.

.