The dollar's role as the world's reserve currency was first established in 1944 with the Bretton Woods agreement. The U.S. was able assume this role by virtue of it then having the largest gold reserves in the world.

The dollar was pegged at $35 an ounce

-- and freely exchangeable into gold at that rate. But by 1971,

convertibility into gold was no longer viable as America's gold

resources drained away.

Instead, the dollar became a pure fiat

currency (decoupled from any physical store of value), until the

petrodollar agreement was concluded by President Nixon in 1973.

The

essence of the deal was that the U.S. would agree to military sales and

defense of Saudi Arabia in return for all oil trade being denominated

in U.S. dollars.

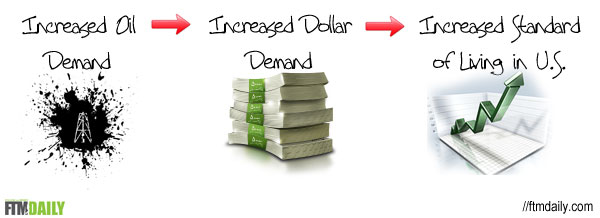

As a result of this agreement, the dollar then became the only medium in which energy exchange could be transacted.

This

underpinned its reserve currency status through the need for foreign

governments to hold dollars; recirculated the dollar costs of oil back

into the U.S. financial system and -- crucially -- made the dollar

effectively convertible into barrels of oil.

The dollar was moved from a gold standard onto a crude oil standard.

U.S.

interest rates were then managed so that oil exporters (who formerly

looked to gold as the basis of their reserves) would be indifferent to

whether they stored their currency reserves, earned from oil exports, in

U.S. treasuries, or in gold. The value was equivalent.

The Fed consistently managed Fed funds rates to keep oil prices steady, even when it required mid-teens interest rates and back-to-back recessions in 1980-1982.

Since U.S. Fed funds rates were managed to preserve U.S. creditors' and oil exporters' purchasing power in oil terms, the system proved acceptable to most nations.

While the petrodollar arrangement worked well for nearly 30 years, the arrangement began to wobble around 2002-2004. . .

Oil prices began steadily rising in 2002 and 2003 while Fed funds rates remained low to mitigate the fallout from the 2001 U.S. recession/tech bubble.

As a result, the number of barrels of oil that could be purchased for a face value U.S. Treasury bond declined sharply. . .

After maintaining a range of 55-60 barrels of oil per U.S. Treasury from 1986-1999, a $1,000 face value U.S. Treasury went from buying 60 barrels of oil in 1999 to under 30 by early 2004.

But what may ultimately be seen to have proved fateful to the

petrodollar system has been the policy of zero interest rate policy and

"quantitative easing" pursued unrestrained since 2008.

Effectively,

energy producers saw that the U.S. economy had now become so dependent

on low interest rates that it could never again manage to keep oil

prices steady relative to U.S. treasuries without blowing up the global

financial system.

The U.S. economy had now become too "financialized" to withstand anything more than a token interest rate hike.

The

petrodollar system, which had allowed the U.S. dollar to supplant gold

as the backing for the oil trade from 1973-2002, was broken.

Energy

producers began to accumulate real assets (such as real estate), and

returned to purchasing physical gold in lieu of U.S. treasuries.

"The oil producers will effectively import capital amounting to $7.6 billion.

By comparison, they exported $60 billion in 2013 and $248 billion in 2012."

re-post